One Iota (or Relationship vs. Doctrine?)

|

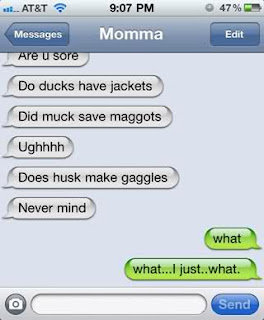

| It's a good thing they didn't conduct the Council of Nicaea by text message. That iota would have really confused the predictive type. |

Recently a somewhat prominent American pastor wrote, 'The nuance of relationship is sadly lost in the world of those who believe doctrinal accuracy (which they have no corner on) is the pinnacle Christian priority.' (James MacDonald). Relationship, for MacDonald, is more important than doctrinal accuracy. But is he right? More to the point, are we even thinking in the right categories?

The New Testament doesn't ever use the word relationship. That's not to say that the idea of relationship isn't there; it's just that it's not a fundamental category of thought for the NT writers. When the biblical authors do want to explicitly address something akin to our concept of relationship, they do have a word to use, but a very different word: koinonia. We translate this word in different ways in English; perhaps the most common today is the word fellowship. Immediately we can see that this word has something to do with relationships, but yet it also has something unique. It's a distinctly Christian word. I don't have fellowship with the hairdresser, the bank clerk, or even with unbelieving friends; fellowship is something we have with God Himself, and with other Christians.

Yet even the word fellowship can be a bit fuzzy in our minds. The way it's often used it can end up meaning little more than a cup of tea after the Sunday service, or a synonym for a local church. So, perhaps an older way of translating koinonia would be more helpful: communion. Communion is an even more Christian word than fellowship. Immediately it makes us think of one of the greatest acts of Christian worship, the Holy Communion, where believers have communion in the body and blood of our Lord. For some reason communion sounds like a stronger word than fellowship; yet they both translate koinonia. This strength of the word is appropriate however, especially in contrast to the light way relationships/friendships are conceived today. You don't have communion by clicking 'like'. And it's this strong idea of communion rather than the weak 21st century concept of relationship that undergirds the biblical writers thinking on the bonds between Christians.

The strength of this idea of communion is seen not only in it's use as an appropriate name for the sacrament, but also in the word we use for the ending of communion. Unlike with 'relationships', communion doesn't simply fizzle out. The end of communion is a big deal; so much so that we call it excommunication - the most severe form of church discipline.

Holy Communion and excommunication point out something else about communion: it's doctrinal nature. True communion involves a high level of doctrinal agreement. To be in communion we must hold and cherish the same truths of the the Gospel, otherwise we could not partake of Communion together. True communion involves holding to the true faith once delivered, for heresy leads to excommunication. Acts 2:42 demonstrates the nature of true communion - it is a relationship that takes in shared doctrine and sacraments, praying together, and coming under that governance of the Church (it is, after all, the apostle's fellowship).

So, biblically, relationship is very important. But the biblical concept of relationship is somewhat different from our 21st century view. Biblical relationships are all about koinonia. That means you can't drive a wedge between doctrine and relationship. Biblically the two go together.

Which brings me back to the theologians and their insistence on doctrinal precision. When theologians are precise, it's not because they want to destroy relationships, but rather, because they care about relationships. While they might not be too interested in being 'friended' or 'liked', they do care about real people and real relationships in the real world. In fact, by their precision they want to 1) grow relationships, 2) protect relationships, and 3) fix relationships. And none of these in the light 21st century sense, but all in the true deep sense of koinonia.

1) Grow relationships

The primary relationship theologians want to see grow and help grow through their precision is the relationship between people and God. Not just other people and God, for theologians too should always be growing in their knowledge of and love for God. The more we know about God, about what He is like and what He has done, the greater our love for Him will be and the stronger our relationship with Him will grow. And what from afar may seem like theological nitpicking may end up having a huge impact on our understanding of our gracious God.

But it's not only our relationship with God Himself that grows as we grow in our knowledge of and love for Him. Our relationships with our brothers and sisters in Christ grow too as we learn together and grow in our common understanding of the mercy of God.

2) Protect Relationships

Probably the vast majority of precise theological distinctions have been articulated in order to protect relationships. However, it's not relationships with the teacher of novelties (or heresies) that the theologians were seeking to protect, but the relationships of the ordinary men and women of God. The theologians wanted to protect the flock from being 'tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine' (Eph. 4:14). They wanted to protect their relationships with God and with each other. The relationships of the whole church tended to get prioritised over the feelings of the false teachers.

3) Fix Relationships

Good theologians, however, usually don't lack concern even for those who are in the wrong. Their goal isn't to prove how right and knowledgeable they are, but to call those who have wondered from the true faith to repentance and restoration to fellowship. The goal is that the relationships of those who are teaching falsely should be restored, both their relationship with God and their relationship with God's people. But that can only come through confession and repentance.

And so, although others may accuse them of nitpicking, theologians have never avoided doctrinal precision, and in so doing, they have not been sacrificing relationships, but rather contributing to true koinonia.

And when anyone today worries that the theologians are being too precise, just look to church history to see the importance of precision. In the fourth century fierce theological debate surrounded one letter. A single iota was of such importance that it caused a crisis in the church. The dispute raged over the words homoousios and homoiousios - was Chirst 'of the same substance' as the Father or 'of similar substance'. Homo (the same) and homoi (similar) only differ by one letter, and yet, as we can see so clearly today at a safe distance, the implications were huge. But, the fact is 'homoi' was originally put forward as a compromise word so as not to damage relationships, yet today we remember it as the defining word of the heresy.

That debate has long been settled, and so today the church unquestionable confesses that Jesus Christ is 'God of God, Light of Light,Very God of very God,Begotten, not made,Being of one substance with the Father' (Nicene Creed). But one letter can make a lot of difference.

Carl Trueman has recently written of those men who fought for the truth in that dispute:

'the foundations for the creedal doctrine of the Trinity were laid by men who thought doctrine was something for which it was actually worth suffering and dying.One letter in the wrong place really is a big deal. One wrong word can have eternal implications. Just like at Nicaea, the church today needs serious shepherds who, for the love of Christ and His people, are ready to stand, like Athanasius, contra mundum: serious men willing to risk all for the faith and true koinonia.

That someone is willing to die for a cause does not sanctify it; but when you add to this that Nicene orthodoxy has been universally agreed upon as important by millions of Christians of multiple races, nationalities and age profile, through sixteen centuries, surely that should give us pause for thought. The questions asked at Nicea were important and they were asked by serious men, men serious enough to risk death for their faith.' (Carl Trueman)